Stamboom Snelder - Versteegh » Saint Theodora of Byzantium (500-548)

Persoonlijke gegevens Saint Theodora of Byzantium

- Zij is geboren in het jaar 500.

- Zij is overleden in het jaar 548, zij was toen 48 jaar oud.

Gezin van Saint Theodora of Byzantium

Zij is getrouwd met Helebolus of Syria.

Zij zijn getrouwd

Kind(eren):

Notities over Saint Theodora of Byzantium

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodora_(6th_century)

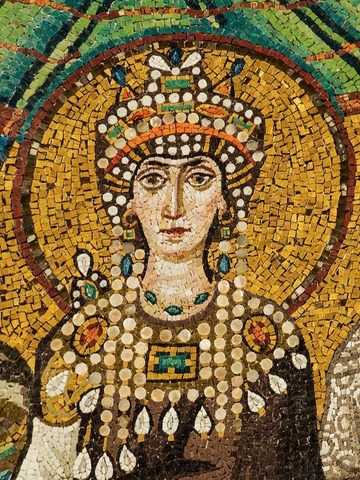

Theodora (Greek: Θεοδώρα; c. 500 – 28 June 548) was empress of the Byzantine Empire and the wife of Emperor Justinian I. She was one of the most influential and powerful of the Byzantine empresses. Some sources mention her as empress regnant with Justinian I as her co-regent. Along with her husband, she is a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church, commemorated on November 14.

The main historical sources for her life are the works of her contemporary Procopius. The historian offered three contradictory portrayals of the Empress. The Wars of Justinian, largely completed in 545, paints a picture of a courageous and influential empress who saved the throne for Justinian.

Later he wrote the Secret History, which survives in only one manuscript suggesting it was not widely read during the Byzantine era. The work revealed an author who had become deeply disillusioned with the emperor Justinian, the empress, and even his patron Belisarius. Justinian is depicted as cruel, venal, prodigal and incompetent; as for Theodora, the reader is treated to a detailed and titillating portrayal of vulgarity and insatiable lust, combined with shrewish and calculating mean-spiritedness; Procopius even claims both are demons whose heads were seen to leave their bodies and roam the palace at night. Yet much of the work covers the same time period as The Wars of Justinian.

Procopius' Buildings of Justinian, written about the same time as the Secret History, is a panegyric which paints Justinian and Theodora as a pious couple and presents particularly flattering portrayals of them. Besides her piety, her beauty is excessively praised. Although Theodora was dead when this work was published, Justinian was alive, and probably commissioned the work.[1]

Her contemporary John of Ephesus writes about Theodora in his Lives of the Eastern Saints. He mentions an illegitimate daughter not named by Procopius.[2]

Various other historians presented additional information on her life. Theophanes the Confessor mentions some familial relations of Theodora to figures not mentioned by Procopius. Victor Tonnennensis notes her familial relation to the next empress, Sophia.

Michael the Syrian, the Chronicle of 1234 and Bar-Hebraeus place her origin in the city of Daman, near Kallinikos, Syria. They contradict Procopius by making Theodora the daughter of a priest, trained in the pious practices of Miaphysitism since birth. These are late Miaphysite sources and record her depiction among members of their creed. The Miaphysites have tended to regard Theodora as one of their own and the tradition may have been invented as a way to improve her reputation and is also in conflict with what is told by the contemporary Miaphysite historian John of Ephesus.[3] These accounts are thus usually ignored in favor of Procopius.[2]

Theodora, according to Michael Grant, was of Greek Cypriot descent.[4] There are several indications of her possible birthplace. According to Michael the Syrian her birthplace was in Syria; Nicephorus Callistus Xanthopoulos names Theodora a native of Cyprus, while the Patria, attributed to George Codinus, claims Theodora came from Paphlagonia. She was born in 500 AD.

Her father, Acacius, was a bear trainer of the hippodrome's Green faction in Constantinople. Her mother, whose name is not recorded, was a dancer and an actress.[5] Her parents had two more daughters.[6] After her father's death, when Theodora was four,[7] her mother brought her children wearing garlands into the hippodrome and presented them as suppliants to the Blue faction. From then on Theodora would be their supporter.

Both John of Ephesus and Procopius (in his Secret History) relate that Theodora from an early age followed her sister Komito's example and worked in a Constantinople brothel serving low-status customers; later she performed on stage.[8] Lynda Garland in "Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527–1204" notes that there seems to be little reason to believe she worked out of a brothel "managed by a pimp". Employment as an actress at the time would include both "indecent exhibitions on stage" and providing sexual services off stage. In what Garland calls the "sleazy entertainment business in the capital", Theodora earned her living by a combination of her theatrical and sexual skills.[3] In Procopius' account, Theodora made a name for herself with her salacious portrayal of Leda and the Swan.[9] Modern feminist sources report that as she was "famous for her wit, she performed as a comedienne at private parties."[7]

During this time she met the future wife of Belisarius, Antonina, with whom she would remain lifelong friends.

At the age of 16, she traveled to North Africa as the companion of a Syrian official named Hecebolus when he went to the Libyan Pentapolis as governor.[10] She stayed with him for almost four years before returning to Constantinople. Abandoned and maltreated by Hecebolus, on her way back to the capital of the Byzantine Empire, she settled for a while in Alexandria, Egypt. She is said to have met Patriarch Timothy III in Alexandria, who was Miaphysite, and it was at that time that she converted to Miaphysite Christianity. From Alexandria she went to Antioch, where she met a Blue faction's dancer, Macedonia, who was perhaps an informer of Justinian.

She returned to Constantinople in 522 and gave up her former lifestyle, settling as a wool spinner in a house near the palace. Her beauty, wit and amusing character drew attention from Justinian, who wanted to marry her. However, he could not: He was heir of the throne of his uncle, Emperor Justin I, and a Roman law from Constantine's time prevented government officials from marrying actresses. Empress Euphemia, who liked Justinian and ordinarily refused him nothing, was against his wedding with an actress. However, Justin was fond of Theodora. In 525, when Euphemia had died, Justin repealed the law, and Justinian married Theodora.[10] By this point, she already had a daughter (whose name has been lost). Justinian apparently treated the daughter and the daughter's son Athanasius as fully legitimate,[11] although sources disagree whether Justinian was the girl's father.

Afbeelding(en) Saint Theodora of Byzantium

De getoonde gegevens hebben geen bronnen.

Over de familienaam Of Byzantium

- Bekijk de informatie die Genealogie Online heeft over de familienaam Of Byzantium.

- Bekijk de informatie die Open Archieven heeft over Of Byzantium.

- Bekijk in het Wie (onder)zoekt wie? register wie de familienaam Of Byzantium (onder)zoekt.

Roel Snelder, "Stamboom Snelder - Versteegh", database, Genealogie Online (https://www.genealogieonline.nl/stamboom-snelder-versteegh/I506018.php : benaderd 15 januari 2025), "Saint Theodora of Byzantium (500-548)".